Hello, readers —

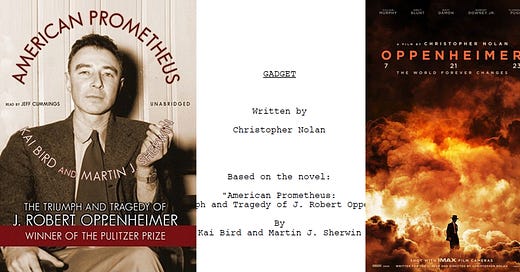

Today I want to dig into Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize winning book American Prometheus and Christopher Nolan’s script. Let’s discuss background on why Nolan chose Oppenheimer as a project, take a look at the structure of the script, and analyze a scene from the film.

While this is history, I’ll be discussing major plot points of the film so if you haven’t seen it, go check it out and then come back.

Background: Why Oppenheimer?

We have Robert Pattinson, in part, to thank for Oppenheimer existing. In an awesome Scriptnotes interview with John August, writer/director Christopher Nolan explains the genesis of the film:

As a wrap gift [to the 2020 film Tenet], Robert Pattinson…gave me a book of Oppenheimer’s published speeches from the 1950s, where he’s speaking to the issue of how to control what to do about this new technology they’ve unleashed on the world. It’s terrifying reading this stuff, reading these brilliant minds discussing how to stop the world being destroyed.

Reading that book of speeches brought back Nolan’s teenage memories of growing up in the UK and the threat of nuclear weaponry in the news. He goes on:

Then Emma and I…spent a weekend with our old friend Chuck Roven…[h]e suggested that I read American Prometheus. He knew the rights-holders…I read it, and it was that wonderful feeling you get where you’ve been interested in something, you’ve been trying to explore it in different ways, but not quite knowing what to do with it, and then you read this book that’s so definitive.

The Pulitzer Prize winning book was just the authoritative source Nolan needed. He decided to “lock into [Oppenheimer’s] point of view on everything” as the first story thread. The other thread would be the objective point of view, the view of Lewis Strauss, which would provide opposition and exposition. Nolan became “very, very obsessed” with Strauss and his relationship with Oppenheimer, saying:

I looked at it from almost the Salieri-Mozart view from Amadeus…about rivalry and the weirdly trivial personal interactions that can drive a very destructive rivalry.1

The Script

With an antagonist and a structure forming in his mind, Nolan came across this passage about 3/4 of the way through American Prometheus:

Strauss’ enmity toward Oppenheimer had only deepened since the 1954 trial. And then all the old wounds had been reopened in 1959, when President Eisenhower nominated Strauss as his commerce secretary. In the bitter confirmation battle, in which the Oppenheimer hearing was a central factor, Strauss narrowly lost, by a vote of 49–46.2

Oppenheimer defenders in the scientific community laid out Strauss’ “reprehensible conduct in the Oppenheimer case” and convinced three senators to vote against his confirmation.

In the book, Bird and Sherwin move on quickly from this scene and a casual reader may not have made a connection. Christopher Nolan, however, is no casual reader; Nolan “immediately grabbed” this idea of Strauss losing the cabinet seat in this very public way and how it echoed Oppenheimer losing his security clearance, which Strauss himself orchestrated in a very private way five years earlier. Nolan said:

As a writer, you’re always looking for those kinds of poetic echoes, those kind of rhyming relationships in narrative. I chased that down.

The parallel moments when Oppenheimer’s security clearance is not restored, and the denial of Strauss’ cabinet position, serve as the climax of the script.

Scene Analysis

For this climactic finale to be effective, the film had to build up to it and highlight the “old wounds” that contributed to the “steady decline” of the relationship between Oppie and Strauss. In Nolan’s words, “two timelines braided together.”

Many scenes are explored from multiple perspectives at different points in the film. For example, the hearing on the export of isotopes.

Here is the text from American Prometheus:

“You can use a shovel for atomic energy; in fact, you do. You can use a bottle of beer for atomic energy. In fact, you do.” At this, the audience murmured with laughter. A young reporter, Philip Stern, happened to be sitting in the hearing room that day. Stern had no idea who was the target of this sarcasm, but “it was clear that Oppenheimer was making a fool of someone.” Joe Volpe knew exactly who was being made a fool. Sitting next to Oppenheimer at the witness table, he glanced back at Lewis Strauss and was not surprised to see the AEC commissioner’s face turning an angry beet-red…

Afterwards, Oppenheimer casually asked Volpe, “Well, Joe, how did I do?” The lawyer replied uneasily, “Too well, Robert. Much too well.”3

And here is the script:

This scene is one example of the characterization in the film that Nolan constructs in the script. But these are words on a page. For it all to work, you need Academy Award winner Robert Downey Jr., who plays Strauss, to bring the humiliation, bruised ego, and vindictiveness of the character to life. In Bird and Sherwin’s text, they describe Strauss thus:

Self-righteous to a fault, he remembered every slight—and meticulously recorded them in an endless stream, each entitled “memorandum to the file.” He was, as the Alsop brothers wrote, a man with a “desperate need to condescend.”4

Oppenheimer is also described as condescending, and Cillian Murphy embodies this attitude of superiority that Bird and Sherwin wrote about:

…for Oppie, condescension came easily—too easily, many friends insisted; it was part of his classroom repertoire. “Robert could make grown men feel like schoolchildren,” said one friend. “He could make giants feel like cockroaches.”5

“The screenplay has to embrace editing”

The build-up to a satisfying climax, the braiding and crosscutting between two timelines, the non-linear storytelling that Nolan has come to be known for, all starts in the script. John August said it eloquently in the same Scriptnotes interview.

You talk about kinetic on the page. You definitely sense the editor on the page. You have a tremendous number of pre-laps and post-laps that make it really feel like this is the experience of watching the movie, that the dialogue is going to anticipate the cut, that we’re going to continue on a little bit after the cut. Things are going to braid themselves together well. Someone who didn’t know might just assume, oh, it’s the editor who moved that stuff around, but it’s very deliberate and clear on the page. You get out of scenes with energy leaning forward that tumbles you into the next scene. That’s why the movie can be the length and the size that it is, and it still feels fast and still feels like it’s moving really quickly.

To which Nolan replies:

Exactly. That leads you to this, I don’t know what you want to call it, guiding principle, whatever, impulse, that says that the document of the screenplay has to embrace editing. For me, that has to be part of my writing process, or I’m not using the screenplay for what it can do fully. It’s like tying a hand behind your back.6

It’s that energy, that tumbling forward, that makes the movie engaging and highly rewatchable, even at a 3-hour runtime.

This has been a bit of a deep dive, so I appreciate you sticking with me until the end. I’ll need to do a part 3 on Oppenheimer because I haven’t even talked about the war and the bomb.

Thanks for reading,

Kyle

I found this entire interview endlessly fascinating and you can listen to all of it (or read the transcript) using this link: Scriptnotes Podcast

Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J.. American Prometheus (p. 577). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J.. American Prometheus (p. 401). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J.. American Prometheus (p. 362). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J.. American Prometheus (p. 401). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Source: Scriptnotes, Episode 622: The One with Christopher Nolan, Transcript (johnaugust.com)

Secret third part?!?! Bravo.